|

I concentrate particularly on the issue of privacy because it is within this context that Friedman et al. ran the only academic studies into the problems of informed consent, and used privacy as one of their justifications for their concern [Friedman et al., 2000,Friedman & Howe, 2002]. I also identify privacy areas as places that could potentially benefit from improved informed consent practices (in the footsteps of Friedman et al.) by examining and evaluating the methods and mechanisms currently used (including those of Friedman's) and showing their limitations. There are potentially many other areas that could benefit from improved informed consent procedures, but it is worthwhile establishing the value of previous research before developing a new theory for general improvement across many areas of information technology. Privacy policies are also more directly related to the problem of End User License Agreements because of their style and structure, and thus could be another area easily able to take advantage of the theory I present in the next chapters.

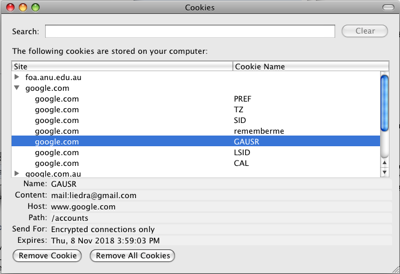

Many Websites use cookies, little packages of information about the user or the Website that are stored in the user's Web browser. In the example shown in Figure 2.3, the Google Mail Website stores a cookie that ``remembers'' my email address (along with a lot of associated data, such as an expiry date for the cookie). These can store all sorts of things, such as a unique identifier, which is often used by advertisement companies to track users across different Websites that use their advertising services and build up profiles of the user to target ads more effectively. These sorts of cookies are commonly considered privacy-invading, or security-breaching, since there is no easy way for the user to know that the cookie has been lodged with the browser. There is often the option to request permission for each cookie, but as you can see, there are seven cookies for just one page in the example in Figure 2.3, so accepting each cookie would start to be an onerous task for even the most careful of users.

Friedman et al. have already addressed some of the issues with informed consent procedures in data privacy and security within information technology [Friedman et al., 2000,Friedman & Howe, 2002], taking an autonomy-justified approach following from Faden and Beauchamp, but aiming specifically at emphasising informed consent as a value for their Value-Sensitive Design paradigm. They do this by targetting cookie handling in the Mozilla Web browser, and writing a cookie manager ``add-on'' to the browser for users that attempts to better inform users of the information being handled by cookies throughout a Web browsing session. The particular areas of concern they noted were that browsers would not disclose useful or important information about cookies to users, such as what data is being stored, how it is being used, how long it would be stored, information about potential harms or benefits for storing the cookies, etc. Also, it was usually detrimental to the Web browsing experience to place restrictions on cookies in a default setting, thus placing the burden of handling each individual cookie on the user. This is a problem that is similar to the End User License Agreement issue, in that even if a user starts out with good intentions when dealing with cookies, eventually the sheer number of cookie requests will cause them to either blindly ``click-through'' or set a default policy that accepts the cookies on their behalf [Friedman & Howe, 2002]. There is increasingly the option in modern Web browsers to set a policy that accepts only cookies from the originating Website (thus shutting out most advertising/third party data mining cookies) which is a step forward from the original default of accepting all cookies, but this is a development that was subsequent to Friedman's research.

Unfortunately the solution presented by Friedman et al. doesn't actually make things much easier for the computer user. The application takes up a large amount of screen real-estate, as seen in Figure 2.4, and still requires a lot of user interaction to manage the cookies, taking up a lot of time from their Web browsing experience. These two problems alone, although solving some of the informed consent issues, would mean that most computer users would rarely actually use the application, because a user's aims when browsing the Web are to browse the Web, not manage their cookies. Most cookies are fairly innocuous, purely used to track a user's progress through a Web site, and not collecting any personal information about the user. Some collect basic information about a user, such as a login and password, storing it so that the user doesn't need to manually log in to a Web site at a later date. Others collect more information, such as personal information required for a purchase or other transaction. Obviously there are differing levels of requirements for consent here, in that a user is not likely to worry much about a login and password being stored on their home computer, but may well be concerned if that is stored at an internet cafe's computer. Similarly for personal information, a user should know what the information is being used for, how long it is being stored, and what information exactly is being stored. Web sites that employ third-party cookies for advertising purposes are also of concern here, since a single advertiser can track the browsing habits of a user that traverses the Web through pages that present that advertiser's cookie-accessing advertisements. These problems would be less of a concern with better informed consent procedures, but the procedures need to be well-integrated into the Web browsing experience, rather than an inconvenient ``add-on''.

Other privacy issues of note in the information technology sphere are the privacy policies that are commonly found in networked software or on Web sites. Usually they are put forward as a set of rights and regulations governing the use of the Web site by the user, and the use of any of the users' information collected by the Web site by the owners. I do not wish to argue with the specific content of such policies, since they are more easily governed by data privacy laws in various jurisdictions, but there is often an implicit agreement entered into without any informed consent procedures at all. It could be argued that with good privacy law, implicit agreements or even no agreements would be necessary. However, this is not a good idea for several reasons: firstly, it would be difficult to derive a `good' privacy law that satisfied the requirements of diverse groups of people (even within the same jurisdiction); secondly, even if such law was developed, people should still be required to waive their normative expectations if these expectations were otherwise to be violated; and finally, it is important for people to understand that their personal information is an important asset, and that they should have an active role in how it is collected, used, and stored. Privacy policies also suffer from some of the same problems as EULAs, that is, that they are difficult to read, long, common to most Web sites, and thus usually ignored [McRobb & Rogerson, 2005] (also section 2.1 of this thesis).

The issue of information privacy highlights the need for more specific techniques that are better suited for technology use than those that exist. These existing mechanisms have been applied post-hoc with little thought as to how users are accessing and absorbing the information, let alone whether or not they consent to the terms of the policies. Too often users give away their information in seemingly innocuous environments only to find that the information is sold to a third party or used in ways they wouldn't want. So the sort of question that needs to be asked is whether or not information collected from users is given under the conditions of a proper consent model within an appropriate privacy-preserving environment. Privacy policy situations could be greatly improved through reconsidering how information is gathered and used by a company, rather than just concentrating on what sort of information is collected and used. As it is, and as I have shown here, the sort of environment needed simply isn't available currently.